Introduction

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, in the closing days of World War II, the first atomic bomb used during wartime in human history was dropped on Hiroshima. Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped, this time on Nagasaki, transforming the city into an incinerated ruins. Most of the 1,532 photographs and two films that make up the “Visual archive of Hiroshima atomic bombing―Photographs and films in 1945” are posted on this archival website. The materials were recorded in Hiroshima between August 6, 1945, and the end of December of the same year by citizens directly affected by the atomic bombing, as well as photographers from Japanese newspapers and news agencies and those accompanying scientific research teams conducting surveys of the situation.

In November 2023, the Hiroshima City government, the Chugoku Shimbun, the Asahi Shimbun, the Mainichi Newspapers, RCC Broadcasting, and Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) jointly submitted a nomination form for the “Visual archive of Hiroshima atomic bombing―Photographs and films in 1945” to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s “Memory of the World” documentary heritage after receiving a recommendation from Japan’s national government. These six media organizations and local government either own the materials or have played a major role in their preservation and utilization. This website is jointly managed by seven organizations, including Kyodo News, the successor organization to the Domei News Agency.

Significance of “by the end of December 1945”

The number of victims of the Hiroshima atomic bombing is estimated to have been 140,000 people (with a margin of error of ± 10,000) by the end of December 1945. According to follow-up surveys of atomic bomb survivors conducted by a certain scientific institution, that period was marked by “high rates of mortality,” and acute radiation effects are considered to have largely subsided by the end of December 1945. This collection of materials documents a wide range of effects from the use of nuclear weapons, including the city reduced to ruins, severely burned victims, and effects from radiation on the human body. Many of the materials are exhibited at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

The collection is limited to photos taken by the end of 1945, but that does not mean the damage from the atomic bombing was over. Rather, the collection represents a record of the beginning of the hardships inherent in rebuilding the city and the health problems that have continued to plague atomic bomb survivors since 1946.

More than 2,000 nuclear tests have been conducted since the end of the war. Estimates show that nine countries still possess more than 12,000 nuclear weapons. What the photos and films remind us is that this reality does not remain in the past. The materials are heritage that must never be lost to the world so they can be used to help us understand the horrors of the atomic bombing and to address humanity’s shared issue of ensuring the experience is never repeated.

Rarity of photos and films of Hiroshima atomic bombing

The photos and films on this website represent definitive primary source material that documents the aftermath of the atomic bombing on the ground, in the moment, from the perspective of the victims and those around them. Considering the standard of living and the scarcity of cameras in Japan at the time of the atomic bombing, as well as the unprecedented chaos immediately after the bombing, the fact that these images exist at all is in itself of unshakable value.

The U.S. military also took photos of the “mushroom cloud” in the sky on the day the atomic bomb was dropped, but those early photos comprised only aerial shots. It was only after September 2, 1945, the day Japan exchanged the instrument of surrender with the Allied Powers after its defeat in World War II, that U.S. military survey teams and other groups entered Hiroshima and took large numbers of photos of destroyed buildings and other structures to record the extent of damage. While their focus was on assessing the explosive power and military effectiveness of the atomic bombing, many of the photos on this website were taken before September 2 and convey images of burned victims and miserable conditions at temporary relief stations, which is a unique feature of these materials.

Also worth noting is that, based on the strong will of the photographers, the materials still exist today, having survived pressure from both Japanese and American authorities and the risk of being dispersed and lost.

Yotsugi Kawahara, who was a member of the photographic team of the former Japanese Imperial Army’s Shipping Command during the war, revealed that, “Photos of the atomic bomb victims, along with many confidential documents, were destroyed by incineration before the Allied Forces occupied Japan at the end of the war by order of the Shipping Command,” and that, “Hundreds of photos were burned, but I secretly kept 25 photos on hand with me.” Shigeo Hayashi, a photographer, also left notes about how he protected the photos from the threat of confiscation by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ), which severely restricted coverage of the atomic bombing, keeping them in his possession. Hajime Miyatake, a photographer for the Asahi Shimbun, mentioned that, “GHQ ordered us to ‘submit the photos related to the atomic bombing,’” and wrote that, “(My boss) ordered all the films to be burned, but I kept them under the floor of my house.”

Classification of the materials

The “Visual archives of Hiroshima atomic bombing-Photographs and films in 1945” are made up of the following eight groups.

The Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima; the Chugoku Shimbun; the Asahi Shimbun; the Mainichi Newspapers; Domei News Agency; Shigeo Hayashi; Shunkichi Kikuchi; Nippon Eigasha

The photos are also classified in accordance with the following three factors.

- Area where photograph was taken: From directly below the hypocenter to the suburbs of Hiroshima, divided into 14 blocks

- Photographers: 27 people in seven groups (two people in a joint filming are counted as one) and one organization group

- Date of photographs: From August 6, 1945 to the end of December of the same year, divided into three periods

Characteristics depending on the “Date of photographs”

Each of the three periods making up the “Date of photographs” has the following characteristics.

1. Photos on August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing – “Mushroom cloud” taken from ground level, affected citizens

These photos represent rare images of the city in flames and wounded citizens in the midst of unprecedented chaos, taken from the ground level by people who themselves experienced the atomic bombing and barely escaped death, as they were in or near Hiroshima when the atomic bomb detonated.

Toshio Fukada had been mobilized to work at the Hiroshima Army Ordnance Supply Depot, located about 2.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. Around 20 minutes after detonation of the atomic bomb, Mr. Fukada continued to take a series of four photos of the mushroom cloud that had formed (TFUKADA0001-0004) by that time. Those were the closest photos to the hypocenter taken of the mushroom cloud. Seiso Yamada took a photo of the mushroom cloud from a mountain located about 6.5 kilometers from the hypocenter (SYAMADA0001). That photo, assumed to have been taken only about two minutes after the detonation, was the earliest of the mushroom cloud from ground level. Four other photographers, including Gonichi Kimura, also took photos of the mushroom cloud (MMATSUSHIGE0001-0002, GKIMURA0001-0003, MOKI0001, TKARASUDA0001).

Mr. Kimura took a series of three photos from a military command building, about four kilometers from the hypocenter, which showed the central area of the city in flames following the extensive fires caused by the bombing’s thermal rays and different uses of fire in the city (GKIMURA0007).

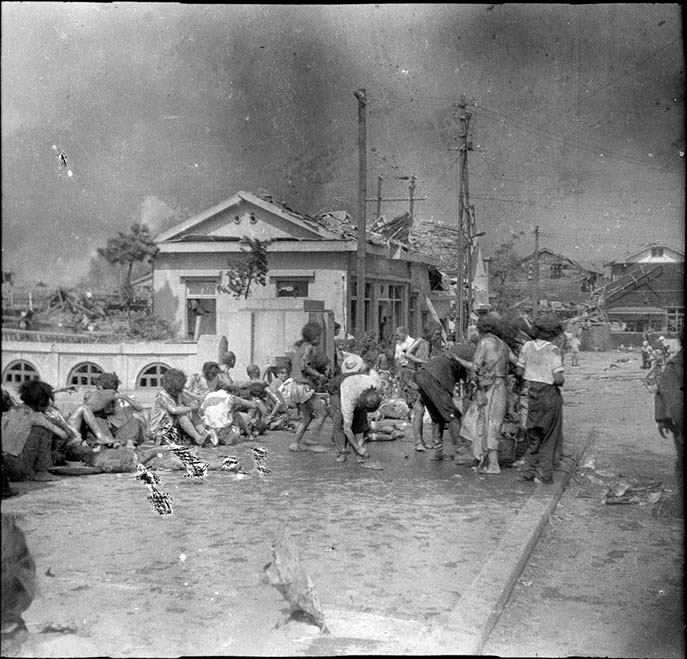

Yoshito Matsushige took two photos at the west end of Miyuki Bridge, about 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, to where many wounded people had fled with hair and skin burned by the bombing’s thermal rays (YMATSUSHIGE0001, 0002). Mr. Matsushige’s photos included images of survivors, such as injured female school students, men and women crouching on the ground, and a mother holding her infant.

2. Photos taken from the day after the atomic bombing until one month later-City immediately after destruction, damage to people from burns and radiation

While there are few photos of the extreme chaos in the devastated city on August 6, the day of the atomic bombing, the Japanese Imperial Army’s survey team and photographers and reporters for newspapers and news agencies from outside Hiroshima Prefecture began entering the city the next day, taking images of the ruined city center near the hypocenter, severely burned citizens, and rescue operations in situations where it was difficult to treat the wounded and carry out lifesaving operations. The photos also showed victims suffering from acute symptoms of radiation exposure immediately after the bombing. The materials, rare with high documentary quality, were taken before the United States Strategic Bombing Survey Team and other groups arrived in Hiroshima and took their many photos.

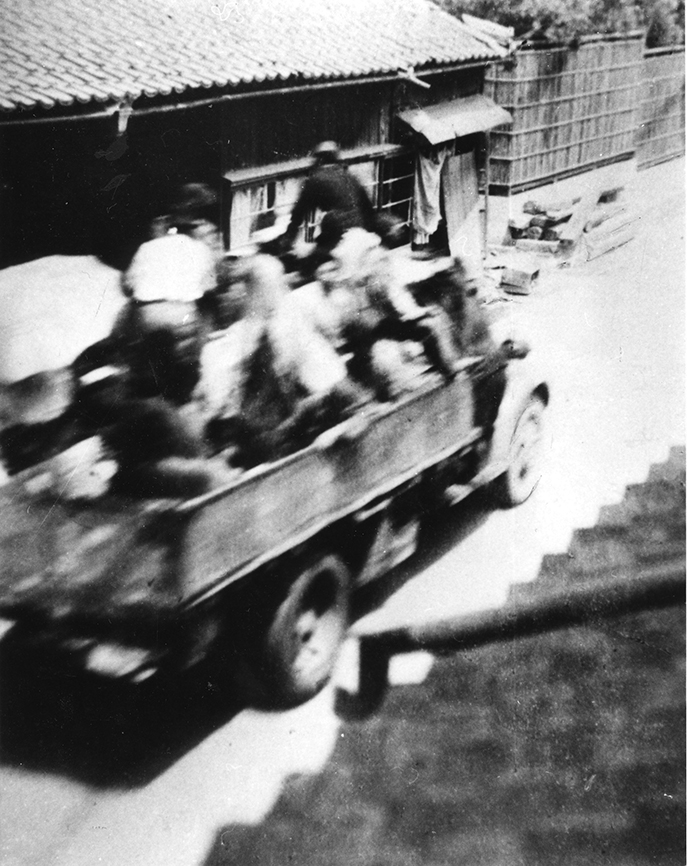

On August 7, Mitsugi Kishida, proprietor of a photo studio on the city’s renowned and bustling Hondori shopping street, entered an area near the ruins of his studio, 450 meters east of the hypocenter, and photographed the ruined landscape of the shopping street (MKISHIDA0002-0004). His photos represent the earliest record of the city center after the bombing. Masami Onuka took photos of severely burned victims with charred skin from the atomic bombing’s thermal rays (MONUKA0001-0004) on August 7, the day after the bombing. Between August 10 and August 11, Hajime Miyatake took many photos of victims at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and elsewhere, including of a woman who had suffered severe burns on her face (HMIYATAKE0060) and a young man undergoing treatment for his burns (HMIYATAKE0067). A photo showing many corpses of soldiers lined up in the ruins in preparation for cremation (HMIYATAKE0076) conveys the reality that countless people did not survive the bombing. A photo taken on August 9 by Yotsugi Kawahara (YKAWAHARA0001) recorded the chaos of a temporary relief station, overflowing with the wounded.

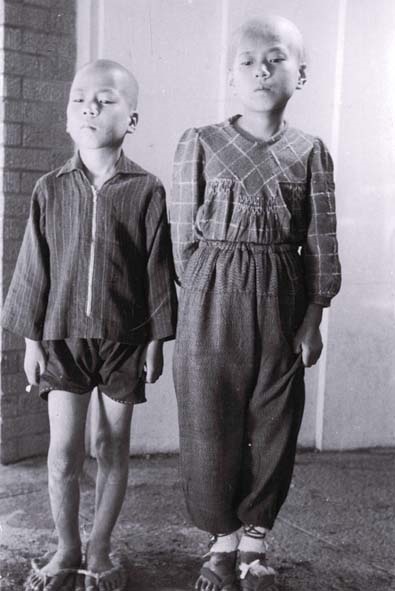

Photos taken by Gonichi Kimura (GKIMURA0011-0017) during the period from the end of August until early September recorded survivors of the atomic bombing who had developed acute symptoms of exposure to radiation, such as spotting from subcutaneous hemorrhaging and loss of hair. Mr. Kimura took the photos upon request from a group of physicians who had come to Hiroshima to conduct a survey of the situation. According to a record of the survey, several of the A-bomb survivors died soon after their photos had been taken.

3. Photos taken from one month after the atomic bombing until the end of 1945-Overview of the destruction and effects from radiation

Hiroshima was a long way from being rebuilt due to the devastation of the entire local community including people’s homes, and survivors were suffering early symptoms of A-bomb radiation. During this period, citizens as well as photographers from newspapers and news agencies and those from Tokyo accompanying Japan’s scientific survey teams left behind many photos.

Shigeo Hayashi’s photo (SHAYASHI0235) symbolized the reality of the fundamental nature of the devastation to the local community. It recorded the expanse of the incinerated ruins in the central area of Hiroshima, including the hypocenter, from a 360-degree perspective.

The photo shows the remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now known as the A-bomb Dome, the Nakajima district (present-day Peace Memorial Park), which before the bombing was an area on the river delta full of houses and shops, and an elementary school building near the hypocenter, a site where many schoolchildren had been killed. Shunkichi Kikuchi’s photos (SKIKUCHI0288–0295) include those of a mother and daughter lying on the floor of a relief station, showing the effects from A-bomb radiation on citizens. The mother was in poor health, with spotting from subcutaneous hemorrhaging and bleeding gums. Her daughter was suffering from severe injuries and hair loss. The mother died on October 14, soon after Mr. Kikuchi took the photo, and the daughter died on November 3.

A man in his 20’s whose photos were taken by Mr. Kikuchi (SKIKUCHI0167-0171) suffered from subcutaneous hemorrhaging and hair loss. Thirty-nine years later, cancer was found in his lungs, throat, and adrenal glands. He died the following year, at the age of 60. It is now known that A-bomb radiation increased the risk of later cancer development. These documentary materials are a record of the beginnings of the consequences of that radiation exposure.